Dr Alexandra Fletcher (or just plain ‘Sally’ for short) is one of the newer members of the senior management team at The National Horseracing Museum.

Sally joined NHRM in 2020 as Packard Curator. In a museum career spanning almost 20 years she previously worked for the British Museum curating the Middle Eastern collections. Her Ph.D. in Archaeology allowed her to travel and work in places such as Turkey, Syria, Jordan, and Arabia. In celebration of International Women’s Day 2021, we asked Sally some questions about her take on women, museums, and horseracing…

Thank you for the chance to speak to you today and ask you some questions about art, the history of horseracing and the increasingly important roles women play within the sport today.

Q. You are a natural champion for diversity and innovation in the arts, with a real focus on the role of women in society – what changes do you hope to bring about at NHRM?

A. I am looking to match the museum’s position with the increasing diversity we are seeing in the horseracing industry itself. So – with International Womens’ Day in mind – I am looking to not only bring out stories about important women in the history of racing but also build our collections to reflect the increasing role of women in the racing industry today. Beyond that, we are also looking to build and nurture relationships with female artists – so two of our temporary exhibitions coming up in the next twelve months or so will focus on important new work by women. More generally I have ambitions to explore social history and diversity in racing, and, for example, reflect on the work of organisations such as Racing with Pride.

A. I am looking to match the museum’s position with the increasing diversity we are seeing in the horseracing industry itself. So – with International Womens’ Day in mind – I am looking to not only bring out stories about important women in the history of racing but also build our collections to reflect the increasing role of women in the racing industry today. Beyond that, we are also looking to build and nurture relationships with female artists – so two of our temporary exhibitions coming up in the next twelve months or so will focus on important new work by women. More generally I have ambitions to explore social history and diversity in racing, and, for example, reflect on the work of organisations such as Racing with Pride.

I am also quietly fascinated by all the work that goes on behind the scenes in the stables and yards all over the UK that culminates in the excitement of race day. For years people have been asking me what goes on behind the scenes at museums and now I want to be the curious one asking questions about the daily hard work that goes into making horseracing one of the largest employers in the UK. I am going to be working over the next year or so to bring this together in a new exhibition at NHRM.

Q. With Cheltenham week approaching, what can you tell us about Dorothy Wyndham Paget, one of the most colourful, frosty, and indeed wealthy horseracing owners, and what her legacy was?

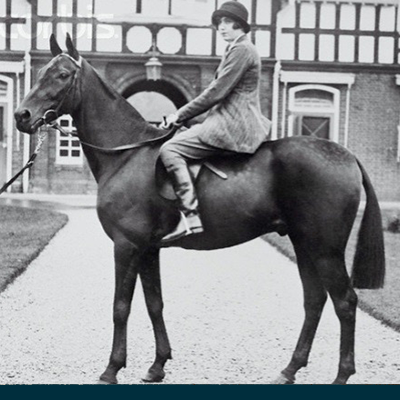

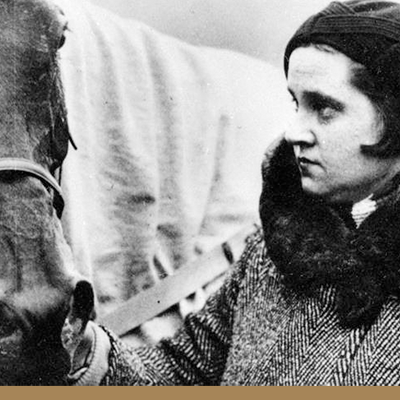

A. Born in 1905, the Honourable Dorothy Wyndham Paget was the daughter of Lord Queenborough and Pauline Payne Whitney, who came from one of America’s most prominent thoroughbred breeding & racing families. Dorothy became notable for her own racing and breeding achievements. A heavy gambler, she lost the equivalent of £90 million pounds over her lifetime but was so wealthy, that no winning or losing bet could have considerably changed the quality of her life.

A. Born in 1905, the Honourable Dorothy Wyndham Paget was the daughter of Lord Queenborough and Pauline Payne Whitney, who came from one of America’s most prominent thoroughbred breeding & racing families. Dorothy became notable for her own racing and breeding achievements. A heavy gambler, she lost the equivalent of £90 million pounds over her lifetime but was so wealthy, that no winning or losing bet could have considerably changed the quality of her life.

Dorothy Paget demonstrated that women could be just as successful as owner/breeders in racing as men. She owned Ballymacoll Stud in Ireland as well as a large number of racehorses in training. Although she worked with many trainers and was notoriously difficult, her horses were very successful both on the flat and over jumps; winning over 1500 races. She was Champion Owner on the flat in 1943 and leading National Hunt owner three times in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. She owned seven Cheltenham Gold Cup winners and four Champion Hurdle winners. Her most famous horse was Golden Miller who won the Cheltenham Gold Cup five times (1932-36) and is still the only horse to win both the Gold Cup and the Grand National in the same season.

I also quietly admire her eccentric lifestyle. At the racecourse, she rejected the fashionably dressed and wore an old coat and no make-up. She spent most of her day in bed, rising at night to place large bets on races. Her bookmakers employed a dedicated member of staff to take her calls. She did not squander all her wealth by gambling however, she took a profound interest in the fate of Russian refugees and financed an old age home for Russian émigrés in France.

It is easy to dismiss Dorothy as having an easy life of wealth and privilege. Beneath the eccentric and at times, terrifying facade, she was a hugely successful owner/breeder who was passionate about racing. She demonstrated to a whole generation of women, they could be who they wished to be and do exactly as they pleased.

Q. What is your favourite object within NHRM’s collection that reflects women’s contribution to racing?

A. I am very fond of a watercolour by Thomas Rowlandson we have on display which shows…

A. I am very fond of a watercolour by Thomas Rowlandson we have on display which shows…

’The Jockey Mrs Thornton in the dress she rode in at York’. Alicia Thornton has been called the first female jockey because she took part in a match race (between two horses) at what is now York Racecourse in 1804. She was in the lead until her horse went lame and she then lost. She did, however; beat the famous jockey Frank Buckle in another match race in 1805. Her achievements are all the more remarkable because she rode in a long dress and seated side-saddle. I love that she did not allow these disadvantages to hold her back. The watercolour captures her standing rather defiantly, hand on hip, holding her jockey cap and whip.

Q . The collections at NHRM date from the 17th century onwards but you used to work in a museum that had collections dating back thousands of years. What can you tell us about horses in the ancient world?

A. I used to work in the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum and given my job at NHRM, I think it’s a very happy coincidence that the Middle East is one of the most important areas of the world for Thoroughbreds in the UK today. All British Thoroughbreds trace their bloodlines back to three stallions brought to England from the Middle East in the late 17th and early 18th centuries: the Byerley Turk (1680s), the Darley Arabian (1704), and the Godolphin Arabian (1729).

A. I used to work in the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum and given my job at NHRM, I think it’s a very happy coincidence that the Middle East is one of the most important areas of the world for Thoroughbreds in the UK today. All British Thoroughbreds trace their bloodlines back to three stallions brought to England from the Middle East in the late 17th and early 18th centuries: the Byerley Turk (1680s), the Darley Arabian (1704), and the Godolphin Arabian (1729).

At the British Museum, I was particularly fascinated by our Middle Eastern collections dating to the Assyrian and Persian periods – that’s roughly 900-300 BC. At that time, horses were really important – not just as a beast of burden and transport – but also as elite, expensive items – a little like racehorses today. Beautifully carved stone reliefs show horses used by the mighty Assyrian army on parade, decked with bells, silken tassels, and gold ornaments. Scientists at the Museum have shown that these images were once brightly painted in shades of blue, red, and yellow – giving us a hint of how amazing they would have looked in the past. There were also tiny intricate models made in pure gold, showing mighty Persian rulers in chariots drawn by teams of horses. I have had the great privilege of holding in my hand’s exquisite pieces, over two thousand years old, which decorated bridles and harnesses made from gold, silver, and ivory. These objects show that our love and appreciation of horses, their beauty, power, and strength, is nothing new.

Q. The current exhibition at NHRM, Sporting Talk features a cracking print featuring a gender-bending heroine who is using the back of a grazing poney (sic) to support her flintlock rifle – what can you tell us about it?

A. I really liked this print of a lady with her ‘shooting poney’ when I first saw it. The look on her face – concentration but with a slight smile – is a delight. She’s clearly relishing what she is doing.

A. I really liked this print of a lady with her ‘shooting poney’ when I first saw it. The look on her face – concentration but with a slight smile – is a delight. She’s clearly relishing what she is doing.

The image is a print made in 1780 after John Collet – an eighteenth-century artist who produced a series of works satirising fashionable ladies participating in sporting pursuits. He showed rather daring women revealing their ankles as they played cricket, skated, or bowled ninepins. Here, the lady is clearly wealthy and has combined her fashionable hat, gown, and heeled shoes with a rather daring man’s hunting jacket accessorised with a powder horn. Collet has captured the moment the gun fires and, unlike the worried groom at left, you can’t help but chuckle in anticipation of the pony’s reaction to the shot.

Q. Tell us about the new exhibition NHRM has planned for later in the year featuring leading female jump jockeys, probably one of the last areas of horseracing that is under-represented by women. Is there a good reason for that…?

A. In our summer exhibition, Mud, Sweat & Tears, we will be looking at the history of Jump Racing and also trying to capture the adrenaline-fuelled excitement of big meetings such as the Cheltenham Festival or the Grand National at Aintree. Jump racing has a shorter history than Flat racing in Britain, but in many ways, it is more widely known. I come from the north-west near Aintree, so the Grand National has a special place in my heart.

A. In our summer exhibition, Mud, Sweat & Tears, we will be looking at the history of Jump Racing and also trying to capture the adrenaline-fuelled excitement of big meetings such as the Cheltenham Festival or the Grand National at Aintree. Jump racing has a shorter history than Flat racing in Britain, but in many ways, it is more widely known. I come from the north-west near Aintree, so the Grand National has a special place in my heart.

I am particularly fascinated by the unpredictability of Jump Racing. When you look at the history of the sport there are surprising winners and losers and stories of enormous courage. Taken together it means the heroes of Jump Racing such as Red Rum, or Bob Champion get taken to people’s hearts and that’s something I am keen to explore in the exhibition.

For me, there is never really a good reason why women are underrepresented in sport or other walks of life. There are barriers to them getting the support, funding, or recognition they deserve, but no good reasons for those barriers exist. Racing in general still has fewer female jockeys than males and Jump racing even more so.

Nevertheless, women are beginning to give the men more of a challenge with jockeys like Bryony Frost starting to make a name for themselves. I think the next decade or so could be a really exciting time for womens’ sport more generally.

As a society, I think both men and women are beginning to expect to see more coverage of women’s sport such as football or cricket. This is why it’s was really disappointing to see that during the second lockdown in November, the Football Association, ruled that the men’s F.A. Cup tournament would not stop, but postponed the women’s F.A. Cup until after the lockdown lifted!

Happily – as horseracing is one of the few sports where women and men compete side by side this hasn’t affected female jockeys trainers and owners even if racing has had to continue behind closed doors.

Q. You recently put together a fascinating timeline of ‘Women in Racing’ for Great British Racing ahead of #IWD2021, who was a standout in that long list for you and why?

Q. You recently put together a fascinating timeline of ‘Women in Racing’ for Great British Racing ahead of #IWD2021, who was a standout in that long list for you and why?

A. I am going to pick a local hero for this one. In 1925, for the first time in its history, the Newmarket Town Plate was won by a woman. Miss Eileen Joel, was the 19-year-old daughter of Mr. S. B. Joel, a millionaire sportsman. The race dates from Charles II’s reign in 1666. This girl definitely ‘can’ and indeed did.

See the GBR article on Women in Racing – here

Q. Whilst you’re new to racing, you are a seasoned champion of equality and diversity, who is your modern-day equine heroine?

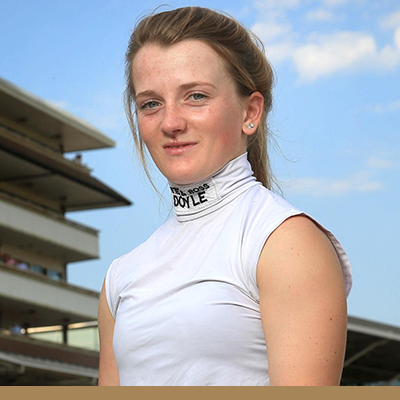

A. Am I allowed two…? Hollie Doyle was my heroine of 2020. She won 151 races last year, was voted flat jockey of the year by her peers, and was also being a finalist on SPOTY. A double win at Lingfield took Doyle to 151 wins for the year, which is a new record for a female jockey.

A. Am I allowed two…? Hollie Doyle was my heroine of 2020. She won 151 races last year, was voted flat jockey of the year by her peers, and was also being a finalist on SPOTY. A double win at Lingfield took Doyle to 151 wins for the year, which is a new record for a female jockey.

When thinking about Hollie though, I also can’t help thinking about Hayley Turner. She is the first woman to have a sustained career as a jockey and I wonder how many of the female jockeys, like Hollie, who are coming through now, would be where they are without having had Hayley to blaze a trail for them to follow.

Hayley was the very first woman to achieve a sustained, successful career as a professional jockey in the UK. In 2008 she was the first woman to ride 100 UK Flat Race winners during a calendar year. In 2011 she was the first female jockey to ride an outright Group 1 race winner in Britain (on Dream Ahead in the July Cup, Newmarket), and then one month later won another Group 1 race(on Margot Did in the Nunthorpe, York). In 2012 she won the Beverly D. Stakes in America, becoming the first UK-based woman to ride an international Grade One winner.

Hayley has been a champion for equality in horseracing for women. She campaigned for financial support for female jockeys to be able to boost their career. She was awarded the OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in the 2016 Queen’s Birthday Honours List for her services to horseracing.

Q. Lastly, you have been bringing in some cracking homebrew ales over lockdown for thankyou’s for your team, what got you into beer?

A. I have been slightly obsessed with women and brewing ever since I heard a radio programme about women and the history of brewing. Until around the 17th-century women were the expert brewers rather than men. I also live in a village with beautiful chalk springs that once fed two large breweries with all the water they needed (and brewing needs a lot of water). The breweries ceased production in the mid-twentieth century but you can still see traces of this brewing heritage all over the village. All of this sowed a seed in my mind that I would like to give making beer a go.

A. I have been slightly obsessed with women and brewing ever since I heard a radio programme about women and the history of brewing. Until around the 17th-century women were the expert brewers rather than men. I also live in a village with beautiful chalk springs that once fed two large breweries with all the water they needed (and brewing needs a lot of water). The breweries ceased production in the mid-twentieth century but you can still see traces of this brewing heritage all over the village. All of this sowed a seed in my mind that I would like to give making beer a go.

I am a very enthusiastic jam and chutney-maker – largely because I can’t bear to see any fruit or vegetables go to waste. Brewing felt like a natural extension of those skills. The first lockdown gave me ample opportunity to get in lots of practice and I now brew about once a month – producing around seven gallons of beer at a time. I brew from grain – so have all this equipment to do it that makes me feel like a bit of a mad scientist. The hard part is waiting for the beer to mature – it takes weeks to be fully ready!